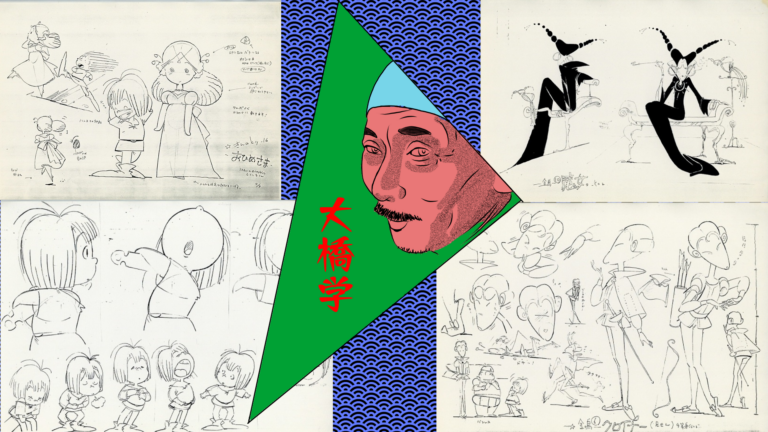

Veteran Toei Animation and MADHOUSE animator Manabu Oohashi, who had been active in the industry since the mid-60s, passed away on February 12, 2022, at the age of 73. In commemoration of his passing, I have written a brief history on his brilliant career.

Oohashi is perhaps best known for being the original character designer for the 1994 Triangle Staff film Junkers Come Home, as well as for directing and animating the “Cloud” segment to the 1987 omnibus film Robot Carnival, but he was so much more than just an artist behind one significant piece of animation– he was one of the animators that inspired generations.

He was a common collaborator of early directing giants like Osamu Dezaki, doing key animation across several series including Ashita no Joe 2 (1980-81), as well as working across several other classics from the era such as Tiger Mask (1969-71), Space Cobra (1982-83), and Venus Wars (1989). This is a brief history on the man named Manabu Oohashi, also known by his pseudonym Mao Lambda.

Oohashi was born on January 17, 1949. Growing up, Oohashi stated that he had a love for gekiga, specifically those featured in the “Hinomaru Bunko” imprint, and he originally wanted to be a gekiga artist, not an animator. However, one day he saw an advertisement from Toei Animation (then called Toei Douga) recruiting staff and decided to apply. At this point, he still hadn’t graduated junior high school (grades 6-8), but Oohashi jokingly declared that perhaps they took interest in him due to his young age (they had seemingly never hired someone so young before).

He graduated from junior high school around 1964, at the age of 15, and immediately went to work for Toei the day after his graduation ceremony. The training period lasted 3 months, and eventually, he was given an option of what production he would like to work on: and the production he chose was the Kaze no Fujimaru movie (1964), where a lot of his peers had also chosen to work.

The new staff members were then led by several veteran animation directors, one of whom was Keiichirou Kimura, who became Oohashi’s mentor. Less than two years later, in 1966, Oohashi made his debut as a key animator on the 10th episode of Rainbow Sentai Robin at the recommendation of Kimura– well, what Kimura really did was bring Oohashi storyboards and tell him to draw the key frames, but nonetheless, it showed his knack for animation. In 1968, he and several other Toei staff members left the studio to become freelance, and Kimura, Oohashi, and several other animators from the group continued to work on projects together.

In the early 1970s, after going freelance, Oohashi became a fan of Osamu Dezaki’s Ashita no Joe, produced by Mushi Production, and subsequently became a fan of the studio as a whole. This, however, was untimely as Mushi Production would collapse in 1973. Despite that, many of the staff members moved around, and eventually, in 1971, Oohashi was given the chance to work with some of them on Kunimatsu-sama no Otoridai. Soon after the end of that production, Oohashi decided that he would follow animators Akio Sugino and other Kunimatsu staff members– which led to him joining studio MADHOUSE.

At MADHOUSE, Oohashi became acquainted with animators like Yoshiaki Kawajiri, and it was here that he began to work on series such as Gatchaman (1972-74). Eventually, however, Oohashi became fatigued and quit animation for about 6 months to work on a picture book he wanted to write (this was his second time “quitting” animation); although, that picture book wasn’t released until 7 years later. After his half-year break, he took on a few jobs as a freelancer until MADHOUSE president Yasuo Ooda invited Oohashi to work with Kawajiri as a freelancing animator on the 1975 series Gamba no Bouken. Oohashi would later say that the series was one of his most referenced points in his career, with the other being his work on the later Ashita no Joe 2.

Around 1980, Oohashi joined Osamu Dezaki and Akio Sugino’s collective group Studio Annapuru, and the staff, together, worked on various Dezaki projects like the aforementioned Ashita no Joe 2. The group became well-known primarily for Ashita no Joe 2, which all members of Annapuru worked on to significant degrees. Oohashi said that if he was going to work on the series at all, he’d have to have done it at Annapuru, and there was no other way he would’ve done it. Somewhere around the time of Golgo 13‘s production in 1983, Oohashi again became a freelance animator and left Studio Annapuru.

One of his biggest projects during his third freelance era was his short film “Cloud”, which was included as one of the 7 films in the omnibus feature Robot Carnival (1987). Commenting on the film, Oohashi says that he doesn’t acknowledge it as the result of his own prowess (despite being the sole director and animator on the short), but nonetheless was glad he seized the opportunity to make something himself.

For the next several decades, Oohashi continued to animate as a freelancer, working across several popular titles like Metropolis (2001) and Air (2005), as well as more recent works such as Children Who Chase Lost Voices (2011), Patema Inverted (2013), and Harmony (2015), and was also a professor of animation and taught a beginner’s animation course at the Laputa Art Animation School.

But not talking about who he worked with, or what his aspirations or inspirations were, the man was an animator, and a good one at that. His key animation drawings across several Dezaki works; his opening animation sequences that, to this day, stand upon the hills of time as they age beautifully; his great emphasis on helping and inspiring others in the industry and proving to be a formidable man even in the presence of his own idols should say more than anything about his skill and what he gave to not only the industry, but to people who have seen his works.

Regardless of what you may know him as, Manabu Oohashi was an important animator in the culture of the Japanese animation industry. While we mourn his loss, we should also celebrate his life and what he gave to that culture.

Source: Oohashi’s Twitter

Further reading: Interview (2001)

Participate In Discussions