The Blu-ray “Final Cut” version of 2022’s RWBY: Ice Queendom is now out, featuring a lot of animation updates including completely revised animation sequences and parts that did not have the time to be properly animated when it first came out. It’s without question that the series had a number of unfortunate production woes during its time and notably featured an intense number of overseas web animators that SHAFT productions or episodes have not seen (either before or since); and also aired during the same time as the studio’s Luminous Witches production–and although the studio works on a rotational system, featuring no distinct production lines, the team was effectively split between these two active projects.

Taking account of the circumstances of its television airing is one thing that I want to do before speaking more in-depth about Ice Queendom overall, but another worthwhile mention is something that I attribute to parts of its failure in marketing–that is, the confusion among both RWBY fans and non-fans alike prior to it airing at all. Little information, either from the Japanese side or the Rooster Teeth side in the US, properly explained what the series was or what it was going to be about. One article cited Rooster Teeth Productions brand manager Christine Brent stating that the series would be “continuity-adjacent” and then described the series as “reduxing” the first two volumes. Geoff Yetter, head of licensing at the company, similarly described it as “canon adjacent” in his March 2022 blogpost and said the same thing–that episodes 1 and 2 would be recaps of RWBY Volumes 1 and 2.

Watching Ice Queendom, you’ll know that’s not true. Episodes 1 through 3 are a recap of V1 and insert a few original elements (such as the character Shion Zaiden and the Nightmare Grimm). So, what’s all that about rehashing Volumes 1 and 2? I don’t know, but whether there was confusion at Rooster Teeth, simply poor wording, miscommunication between the Japanese and American teams, or so forth–I think the marketing for the show could have done a lot better in making things clear to get more interest in the series. Ambiguity can be interesting, but this is not such a case. Gen Urobuchi (Nitro+) conceptualized the story, but actual composition and scriptwriting duties were given to Tow Ubukata, whom director Toshimasa Suzuki and Urobuchi had worked with prior. Ubukata then took Urobuchi’s concepts and wrote them out into the form of an organized story and screenplay–by then, they only had about eight episodes worth of content with twelve planned episodes, so it was then decided that a recap of sorts would be included in the first episode, and episode 12 was thought up around the same time as well.

Ubukata and Urobuchi mention that the first three episodes are basic retellings of Volume 1, and that they ultimately cut out a lot of content–so rather than persuade the audience to simply take the content of the “redux” as is, they hoped there would be incentive to view the first volume as well. In this sense, the anime hopes to introduce the characters within the timeline that they exist and establish the characters’ strained relationships during that time period, given that as of the series airing Volume 9 had already been completed. Obviously, as a discussion, this is going to go into spoilers for both Ice Queendom and RWBY.

Episodes 1-3: Revisiting RWBY

The main problem with the first three episodes is not the intent of the writers in including these episodes, while also serving to lightly introduce more and more of what will eventually become the main elements in regard to Ice Queendom’s narrative, but rather the fact that they seem to be disjointed in both their own slice of the narrative and their connection to the later parts. While I’ve established that these episodes are not meant to replace RWBY Volume 1, compressing certain narrative beats to their most important or most simple is a smart writing method of introducing to the audience what is going to be the most important aspects of the coming series.

It’s true that the series does capitalize on this somewhat: for example, extra care is given in the first episode to introducing Weiss Schnee, her relationship with her family, and simply building up the world as the original RWBY series did. Director Suzuki is able to wonderfully encapsulate in this first episode (which he storyboarded and directed) Weiss and her relationship with her family through simple and effective visual storytelling, and the focus on her is to the betterment of her overall character and audience’s perception of why she is “that way.” In the scene where she’s heading to her test and walking with Klein, the camera moves past a portrait of her family on its lonesome, shows a bird’s eye shot from above, then cuts to a far-away pan of her mother drinking while seemingly isolated from the rest of the world, and then we see a cross-armed Whitley. Little things like this are where Suzuki works his best magic, and it builds a little bit on certain details of Weiss that the original show didn’t at this stage. Given Weiss is the subject of Ice Queendom and Ruby Rose is the (somewhat) titular protagonist, the series’ (somewhat) hyper-fixation on them is sensible.

However, episode 1 also significantly cuts things like Blake Belladonna’s introduction into just this little piece of information that you get about her relationship with Adam and the White Fang, and though the next few episodes have discussions regarding this, it offers little to a newer viewer and doesn’t competently condense what would otherwise be an important part of Blake’s character for the remainder of Ice Queendom and its themes. It makes sense to a point given the focus on Weiss and Ruby, but it doesn’t work when later elements of the composition focus on Weiss and Blake–specifically because of their indirect relationship in the names and people they belong or belonged to. That minor introduction to Blake and Adam certainly doesn’t serve the later attempt for any new fan, and I think it struggles to keep the interest of a fan who has already witnessed that portrayal in the main series which fleshes those thoughts out far more. As I said, I understand this isn’t meant to replace viewing RWBY Volume 1, but there’s seemingly a misguided focus on the complexity of Blake and Weiss’ perceptual problems. Yang Xiao Long is also mostly ignored throughout this process.

Shion is introduced as an original character, and they’ve honestly got a pretty cool design and Semblance. I suppose it’s sort of the way of introducing something more… “Japanese”, of sorts; though, Urobuchi’s idea of using an acoustic coupler and rotary telephone to communicate with people in the dreams is pretty cool. I can’t help but think of the Medicine Seller from Mononoke when I see Shion’s design, to be honest. But that’s a compliment.

Aesthetically speaking, I think the team captures the appeal of the series in most of the design work for the most part. Nobuhiro Sugiyama (SHAFT) adapted Huke’s re-adapted designs for 2D animation rather well; as did Kenta Yokoya in adapting the Grimm designs, Yoshitomo Hara doing the weapon and mechanical designs (Ruby’s scythe loks great), and so forth. Of course, my favorite part of the entire aesthetic comes from the backgrounds directed by Takeshi Naitou (Studio Tulip) and the composite effort of Takayuki Aizu (DIGITAL@SHAFT). I wouldn’t say it’s either of their best, but undoubtedly the series is given a unique and appealing look respecting the original work and re-envisioning it to fit the new anime’s style. Many of the environmental backgrounds are given a soft, fairy tale-esque look, and Naitou’s team often uses thicker brushes for the linework both outside and within interiors, and the room Weiss fights in has a slightly gothic flare. The city’s western architecture combines simple elements and warm colors, and even a couple of light flares for added touch.

Some fans of SHAFT’s brand may notice that it doesn’t lean very heavily into their usual style, but this was a conscious decision by director Suzuki, who himself is influenced by studio monolith Akiyuki Shinbo and the late Ryuutarou Nakamura, the former of which can be clearly seen in the ending he directed for Dance in the Vampire Bund (2010). However, that isn’t to say Suzuki totally inhibited the endeavors of the staff who come from such a background. Aspects of SHAFT’s modern self-indulgent style this far in can be mainly attributed to certain processing decisions–assistant director Kenjirou Okada (who directed episode 3) is quite fond of contrasts between brightly lit backgrounds and darkened foreground characters or objects. Okada’s episode (storyboarded by visual director Nobuyuki Takeuchi) has a few instances of this, and one of the Blu-Ray corrections for this episode is the addition of a black foreground smack of a ceiling fan in this scene to lead the eye in the scene. The color designs for the characters also seem a little similar to the style of the studio’s other project of the season, Luminous Witches, and that’s of course due to color designer Hitoshi Hibino (SHAFT) being responsible for both. Side note: Okada’s “chief director” (チーフディレクター) credit in this instance is equivalent to “assistant director.”

These episodes don’t have very many animation or art corrections for the Blu-Ray release. Many portions were already corrected for the TV release after the June 2022 pre-broadcast, but there are still a number of redrawn scenes and corrected processes. One example, of course, is the Hiroto Nagata-animated scene in episode 2–that’s where Team RWBY defeats the Nevermore–which has fixed textures on the rocks. A couple of places have redone backgrounds, but it’s not too significant this early on.

Episodes 4-11: Ice Queendom

Before Ice Queendom, we’re given an insight into the basic premise of how the Nightmare Grimm works when one infects Jaune Arc. It plays into his lack of confidence and it’s an effective introduction, and Weiss slowly develops symptoms of it throughout episode 3 as she sees a double of herself and we see it on her body giving it a little bit of a horror feel before cultivating into the end of the episode.

As Ruby is tasked with scouting the nightmare, we’re introduced to its wacky stylization and depiction of Weiss’ thoughts, fears, relationships, and so forth. In other words, its incoherence plays to the fact that it is a dream that is personifying her inner turmoil: that is what the nightmares are. According to Urobuchi and Ubukata, it was Huke’s idea to redesign the characters in this world; so, Weiss becomes what many say looks like Esdeath from Akame ga Kill and Ruby gets a cute snowboarder outfit. That’s a lot of fun and all, though the core aspect of Ruby’s redesign is in her scythe, which is represented incorrectly and basically a nod to Weiss not understanding its logic, thus establishing a partial logic for Weiss’ Ice Queendom. When writing the series, the two were also able to make use of production and alternate world designer Rui Tomono’s concept art to discuss with some vision what was in mind for the visual style.

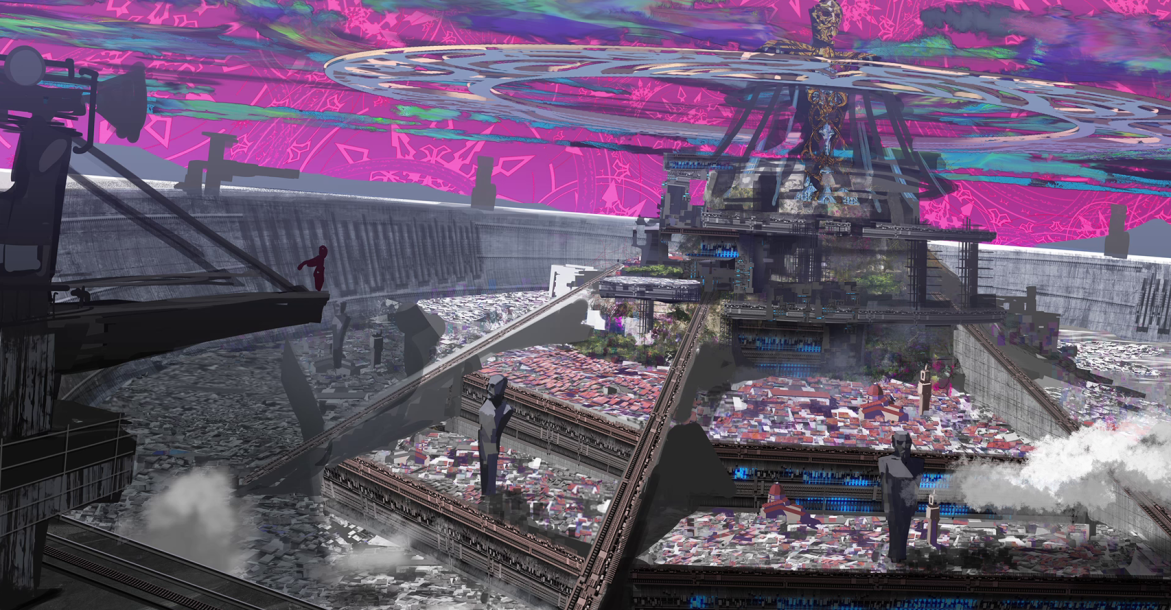

Ice Queendom does suffer a little bit in that regard. Of course, you can’t expect a television animation production to necessarily match concept art–just like you can’t expect a video game to match the concept art–but I there’s something striking about the portrayal of the city in the concepts compared to the anime. It feels much more like a living being with such a scale, where all of these different sectors have people doing things representative of a part of Weiss. It may have been that there wasn’t time to polish the artistry further, as the Blu-Ray does in fact make many corrections to the backgrounds; however, Ice Queendom’s city feels a bit devoid of life in that regard. Even when Tomono’s concept feels lifeless and still, there’s a lack of comfortability that comes with those drawings that the final product certainly does not have. There’s an overwhelming sense of isolation or (as I would describe) anxiousness. I have an extremely bizarre analogy: some of Tomono’s art reminds me a little of the way Infinity Ward depicted the ghost city of Pripyat in the original Modern Warfare video game. The anime neither fully realizes those expressions of coldness in the art, nor makes the dream world feel like a visceral, living, and overwhelming entity. I feel like Big Nicholas being at the heart of the city was meant to hammer in that idea that the city is a living, breathing being of Weiss’ dystopic nightmare bringing to life expectations from narcissists and her lack of proper companionship to any degree.

Aside from workers who slave away for “the Empire”, people from the inner circle, including Weiss’ own mother, are silhouettes without form, simply plastered against the planes of walls and the ground beneath. I don’t know if this was necessarily inspired by RWBY doing something similar (but for resource reasons), but it’s effective in distancing them far from Weiss’ life. They are faceless and something that she cannot see eye to eye with, or that she doesn’t notice as even being there.

Episode 4 of Ice Queendom also has a cornerstone facet of “SHAFT” that I wish Suzuki did use more of. I respect the decision to shy away from the ordinary studio’s stylistic tendencies, but this episode was storyboarded by Midori Yoshizawa (partial series and assistant director for Magia Record) who smartly utilizes a completely different quality of the studio’s productions than the quirky visual appeals that many seem to think are the sole basis for their foundational style: that is, “efficiency.” That’s pretty vague, so let’s look at an example: Ruby contacting Zaiden. Ruby sticks her hands in her pockets, and we cut to just an image of the coins. Then we cut to her holding the coins in her hand–no necessity in showing her pulling them out. When she flicks the coin, it cuts to an underside shot of her hand doing such; and when we hear Shion’s voice, it’s simply illustrated through (what I’m calling) radiographic lines. Without needing too much character acting or overextending the resource demand, we’re able to fully comprehend the visual storytelling of the scene just by the scenic composition and tempo. Now is also worth mentioning editor Rie Matsubara (Seyama Henshuushitsu), who is in charge of the series and also a very close collaborator of the studio; and the editing in such sequences reflects that quite well.

In a way, I think you can connect this philosophy in a scenic direction as being like the “Gestalt principle of closure”. While this principle is primarily associated with visual design and panel or page storytelling, it can similarly describe works in which the audience fills in the gaps between actions simply by understanding the pattern or in-between actions that aren’t shown. A couple of other episodes occasionally do similar things, but these also come down to the most tuned-in to the visual lexicon–production issues or nay, I think the series would have benefited from more insistence on this kind of theater given its excellence in efficient storytelling. Similarly, episode 6, storyboarded by longtime Zaregoto and Fire Force‘s Yuki Yase and directed by Madoka Magica’s Yukihiro Miyamoto, also has a scene where Yang calls Blake and Blake is personified as a contact on Yang’s phone with a monochrome red background–the sound design here also doesn’t make use of Blake talking, and instead replaces her voice with a sort of static noise.

When it comes to the writing, there are a few issues I take with Ubukata’s script: mainly that, at least in episodes 4 and 5, there’s too much spoon-feeding the audience. There’s always dialogue confirmation of something that can already be figured out by watching. When Team RWBY eventually sneaks into the city without using any coins, Yang confirms that they’ve snuck in without having to use any coins. It’s a nitpick, but there are several moments where similar things occur that I thought became repetitive in a way that did not keep interest. More importantly, the written exposition also can be a slog to get through for partially the same reason.

Ice Queendom has established a number of cool concepts, but it doesn’t use them effectively and instead drags the whole thing out. Weiss has doubts about what she’s doing even while under the control of a nightmare, but then changes her mind and doubles down in a way that I can’t describe as anything but awkward. Certainly, the doubts and issues plaguing her mind are reinforced by a powerful Grimm, but it’s not shown as anything but a whim in writing, I feel. Of course, I may be overlooking something in this particular example, so let’s take a look at another. The change in character designs for Team RWBY and Jaune reflects Weiss’ perception of everyone, yet the only RWBY protagonist who feels underutilized to that end is Yang. Blake’s outfit is related to her being Faunus, Ruby’s is about her behavior, the weapons are changed because Weiss doesn’t understand them or whatever, and Yang is just there. Throughout all of Ice Queendom, Yang simply exists as a minor character helping out, it feels. Of course, Yang and Weiss haven’t had all that much time to interact, but then in that case it’s not as though she’s close enough to Weiss that theoretically someone like Professor Ozpin or Pyrrha Nikos couldn’t instead go. Of course, Jaune went too, but you can… sort of rationalize that.

The different Kleins and prop personifications (shoutout to prop designer Kio Edamatsu), the myriad of little Weiss’ locked away, Jacques Schnee existing as more of a looming overlord or idea than an actual person, and the idea of the train always doomed to never reach the city, and so forth are a variety of great concepts that don’t all get the same level of love. Of these, it’s the little Weiss’ who feels like the most fleshed-out idea of all of these, but they don’t exactly work in tandem with other aspects to bring out their appeals. As a side note, one of the series’ biggest production flaws seems to be in its pre-production. Edamatsu’s designs received big revisions in the Blu-Ray release, indicating that the designs themselves were unfinished; and coupled with many other design (setting) changes in earlier parts and now the Ice Queendom portion insinuates problems before production itself began.

This becomes truer as we head into episodes 8 and 9, specifically when Ruby herself becomes affected by a nightmare and is immediately saved by Jaune. While we do get to explore a small portion of Ruby’s insecurities and the way she views Weiss, this part just feels entirely too rushed. Instead of dragging everything else out, wouldn’t it be more interesting to discuss more of Ruby’s emotions here? There’s a lot that could be done, but it’s instantly negated for the purpose of moving Ice Queendom down the train tracks and ultimately feels like an underutilized idea.

On that note, the ending to episode 8 is haunting. Ruby wakes up, confused as to what’s going on, and is then greeted by her friends congratulating her for defeating the nightmare. Then, her father and others show up, and she becomes confused. At the center of a circle formed by her peers and family, a blindingly bright light overhead shows, and there’s a warp pan where everyone around her is shown–but all of their faces are obfuscated in darkness, and their hands shown simply clapping for her. Assistant director Okada was in charge of processing this episode, though the storyboards are by studio regular Kei Ajiki (who is also the character designer for Bandai Namco’s recent Birdie Wing). Suzuki’s team is quite consistent in the execution of these creepy and psychological scenes.

Blake’s identity with the Faunus is also a big portion of this final act of the story, as well, as she comes up with a plan to let the nightmare infect her so that she can become strong enough to fight against Weiss. Great, so we have a cool idea again, and we’re going to have her encapsulate an identity that takes the form of Adam. Great. But this is what I meant when I was talking about the first episode not doing enough with Blake and Adam: as someone who’s kept up with RWBY, I’m well aware of the significance in her donning a nightmare that effectively combines her with Adam’s sensibility and why it’s a powerful message as far as her willingness to save Weiss; but in the context of Ice Queendom, which spends time contextualizing Weiss, there’s little emphasis on this facet of Blake’s character outside of the literal one scene we received with Adam and bits and pieces that don’t formulate a full picture. One of the aspects of the series’ climax comes down to Blake embracing her previous identity for the sake of being able to embrace her newfound friends and team, but the emotional payoff feels relatively nonexistent.

Episode 10 of the series seems to have been the worst as far as production goes, given it has 3 credited storyboard artists (including the episode’s director) and was beyond unfinished–the Blu-Ray version not only has an incredible number of corrections, but it also adds in a number of new animations that were completely absent in the original TV broadcast. While not everything got corrected (this goes for every other episode too), it’s an incredibly different experience and well-worth the number of retakes it received. Ruby has finally come to beat the nightmare as the rest of the gang defends themselves from its ever-growing power and the time limit in which they have to do so.

And that’s how Ice Queendom ends in a nutshell. Though there are a number of cool action sequences, including two by main animators and SHAFT’s current action aces Nagata and Kazuki Kawata, I do think it’s a bit anticlimactic narratively. Yang’s fight is simply her against a big strong thing that she punches. There’s little focus on her, and her part in the climax comes down to just a fight. Which is fine, but everyone else is shining in some way, so relative to the others she feels overwhelmingly unnecessary aside from defeating Big Nicholas, to put it bluntly. Jaune is acting as a bit of a knight (against Knight Jacques)–he’s clumsy, he’s kind of weak, but in a way, he’s living up to the idea that Weiss exaggerates him for; whereas Ruby is going for Weiss’ heart; and Weiss and Blake are dueling while exchanging words about their perceived biases and whatnot. Ruby also uses her silver eyes for the first time, and Yang is able to pull Blake away from her nightmare; then, “RWBY” defeats it as a team.

It can be a bit difficult to write about these characters because it’s a bit of a retrospective and the writers have to be keenly aware of not overextending their reach if they want it to exist within RWBY’s canon. They can’t exactly tackle issues that aren’t subjects until later on in the series, otherwise the character chronologies would be inconsistent. I wonder if that’s one reason why Ruby’s confidence isn’t focused on much in episodes 7-8, because it’s a big part of her character in later volumes of RWBY more than it is here, which I feel makes the dream within a dream bit even more of a confusing addition to have. And that’s why it’s hard for me to put into words how I feel about it: it’s a bit of an oxymoron, but it feels rushed yet way too slow. It glosses over genuinely fascinating ideas but still manages to feel like there wasn’t enough content.

Having a single subject character is interesting but intertwining them with the other protagonists and making their relationships interesting is essential for RWBY. It’s been mentioned in a few interviews that Rooster Teeth wanted the team to have fun with their work, and it looks like they did, but maintaining “canon-adjacency” feels like an inhibitor in that regard. Of course, that’s an opinion from an audience member and not someone who worked on the series; though, the producers said they were open to doing more for the series if it was popular enough. I don’t know if there will be more, but I would hope for something broader if there is. (Though, honestly, I think it would be totally fine to ignore the canon and simply make an interesting one-off story with the characters or setting.)

Episode 12: Studio Unhinged

The review for this episode is by itself just because it’s weird. It’s Ubukata’s most interesting writing, but it also feels like director Suzuki completely stopped directing in a more “orthodox” manner.

This episode coincides with episode 1 of RWBY Volume 2, and we’re shown the gang as they enjoy themselves in their dorm room and establish the newfound connection mainly between Weiss & Ruby and Weiss & Blake (and a little with Yang & Blake). We also say goodbye to Ice Queendom’s original character Shion. I suppose they were never meant to be a particularly complex and fleshed-out part of the series, especially within a single cour that isn’t focused on them as a character–but there is a little bit of disappointment because they have a really cool design and abilities. Episode 12 does give a little bit more to Shion as a character and makes them feel as though they exist in the world of RWBY, I just wish there was more focus on them for someone who sort of exists as a device for a narrative element and seemingly nothing more.

There are two main highlights to this episode. The first is the conversations that Ozpin has with Ruby and Blake when he individually pulls them into his office to talk to them. When I say that Ubukata’s writing is most interesting in this episode, this is what I mean. Rather than being held back by the scenario, the way he’s written Ozpin’s curiosity on the matter of Ice Queendom‘s nightmares is intriguing, because he’s adding to the overall “canon” of RWBY in an interesting way: through visual direction and his writing, we’re made aware of the fact that he knows about Ruby’s silver eyes. His inquiry isn’t based on malicious intent, but rather curiosity of things that she does not. The audience is aware of her eyes, though Ruby herself exemplifies that she does not. With Blake, we have a genuinely moving conversation regarding the Faunus: to those who aren’t as indoctrinated into RWBY thus far, it’s an insight into Ozpin’s perceptiveness, and that he knew she was a Faunus the entire time. This sparks a discussion about why she hides herself since Beacon is a place that does not discriminate between Human, Faunus, or otherwise. But this is only on paper, as Blake mentions that such equality between species and races exists in name and that the social structures of the world–the Academy, the country, and so forth–dictate metaphorically unspoken divisions. He asks if there’s anything else she’s hiding, which she says no to, and they disperse. Afterward, Weiss is waiting for Blake, and they walk and talk about themselves, the Ice Queendom stuff, and have a short heart-to-heart moment.

These scenes are powerful not just because of the genuinely evocative writing, but also because they’re coupled with a grandeur of visual storytelling. This episode has two storyboard artists and two directors: Naoaki Shibuta (who did both roles), and Yoshizawa/Okada (respectively). Now, it’s a bit of a guess as to who is responsible for which segment, but if the credits are in the correct order, then that means Shibuta (a rookie director belonging to the company) would be in charge of this first half.

In the first scene, Shibuta does things relatively normal and focuses on the efficiency I mentioned in episode 4. Want to show Weiss making coffee? Then just do this. It’s very simple and it works. By the time we get to Shion’s goodbye scene, we’re already keenly aware that Shibuta is economically approaching how to visually stimulate many of these scenes while also telling that story. That’s all great, and then we get to Ozpin turning his head, cutting to his eyes, and then finishing the head turn. It’s much of that same endeavor seen in works like Madoka Magica and Monogatari. Shibuta has been at the company since about 2011 and started doing minor directing work in 2015, so I’m sure he has a very strong influence in that regard.

When we get to the interrogation scene, there’s as much focus on close-ups of his eye. We’re in Ozpin’s office which has a very peculiar setting design, and as he begins to question them about anything “weird” that happened to Ruby and if Blake is hiding anything, the gears turning in the ceiling blanket the two of them in shadows, as though their conversation is so secretive that it warrants physical closure from the outside world; and when Ruby dispels the idea that anything weird has happened, the shadows move away. She’s not necessarily lying, because she doesn’t quite understand what he could be referring to and she’s not conscious of her silver eye power in the dream. When she leaves, Shibuta again focuses on the economic representation of the scene moving forward: rather than spend time with a drawing of Ruby in the elevator, we simply get a shot of the elevator pad with each of the floor numbers lighting up as it moves down, and then we cut to the doors opening to Ruby.

Blake’s segment has the same storytelling qualities, though it feels much more oppressive with the involvement of the camera and certain processing choices. Even before obscuring the two in shadows, the camera has a particular pan on Blake’s own shadow, as though to portray that Ruby truly did not have anything to hide whereas Blake is actively lying. Ozpin’s figure itself becomes a sort of shadow as he’s drawn in shadowless (kagenashi), as though he himself is completely truthful yet at the same time not (conscious RWBY lore visual direction or coincidence?). Worm’s eye (low-angle) shots, focus on just his mouth, and profile shots of Blake from just the nose down set the tone wonderfully–and there are some really, really great drawings of Ozpin staring down the camera.

For as many problems as I feel that the narrative of Ice Queendom has, the succeeding segment does feel like a properly cultivated conclusion as far as its execution. Though Team RWBY is undoubtedly going to go through more tumultuous moments, what they’ve come to do is accept each other for their differences and remind themselves of their similarities and characters. Ultimately, that is what Ice Queendom is supposed to be about. It’s a story of prejudices and inherent biases that can fester in echo chambers of unchallenged beliefs leading to questionable cognitive perceptions, narcissistic self-beliefs, and a downward spiral. Of course, these ideas aren’t limited to ideas of bigotry that RWBY attempts to tackle.

Jaune himself is also shown to have had a bit of a character arc throughout the series. He is often plagued by his own self-worth and abilities, yet Pyrrha Nikos’s belief in him in both the dream world and in his actual life sees the good of his character and his potential. Her support is integral to the development of his self-realization, but it is through his own power that Jaune acts for the purpose of something like saving Dream Pyrrha and trying his hardest to be the best version of himself still supported by Pyrrha.

Then, the famed food fight.

I think it’s worth keeping in mind that aspects of Ice Queendom that “remake” scenes from the original series don’t seem to try to be “better” than the original. In no way do I feel as though the staff are attempting to recreate the series’ charm perfectly because that’s ultimately impossible–Monty Oum was undoubtedly a director and animator who can’t just be replicated, especially when it comes to his choreographed and solo-animated fight sequences. Episode 12’s food fight reflects that aspect the most. Rather than remake the food fight scene-for-scene, the anime makes it cool in its own way, paying homage to what Oum created, while also serving as a somewhat thematically resonant conclusion and separate perspective from what the original food fight was.

What I mean by that is: that RWBY‘s food fight we can describe as being told in an objective light. The audience views the fight from every perspective: there’s a winner for each individual battle, a winner for the entire fight, and a focus on the fun and coolness of the movement, actions, and characters. The anime shows a similar coolness, both in and out of the sequences that aforementioned talents Nagata and Kawata key animated; but the story being told here is in a subjective light through the lens of Ruby. When Weiss is hit by the cake, it’s funny and we laugh, and then the camera pans down from a shot of the tall window to her ominous figure centered in the composition and a creepy close-up of her face. Everyone thinks she’s going to be mad, but she says that it’s time for the food fight. That’s powerful here and in the original because her character has a similar change of heart in RWBY, though Ice Queendom works toward the same goal in that respect.

The fight begins the same as in the original, with a traveling camera moving away from Team JNPR at one end of the hall; and while Ice Queendom made use of Jeff Williams’ songs (the original composer for a majority of RWBY) as inserts throughout various scenes, this is one of the ones that doesn’t do that. The original features one of Williams’ epic rock pieces, yet instead we’re greeted (a little earlier) by a softer, more nostalgic song. This isn’t to the effort of nostalgia-baiting, otherwise I think they would’ve used one of Williams’ songs, but rather to recontextualize the scene.

Some elements of the scene are moved around and ultimately compressed (it’s shorter than the actual RWBY fight), but in the middle of it, after Ruby gets knocked back, the narration takes over on top of the music as Ruby opens her eyes to bear witness to the friends she has and the people they were able to protect. The camera itself “opens” as she opens her eyes–by that I mean, the aspect ratio–and each of the characters who are fighting smiles at each other. Rather than finish the fight off, we instead get dynamic stills of Team RWBY and Team JNPR (drawn by Nagata) which leads to a final beautiful shot of Team RWBY laughing together (drawn by Japan-based Russian artist Ilya Kuvshinov).

It feels like it fully respects what Oum and Rooster Teeth Animation’s staff were able to build with their small team and relatively small budget (but inspired ideas) while also making use of elements that only anime can offer, both in a general sense and more specifically with what this team was capable of illuminating. And that’s why I don’t mind these little “remake” segments–because they’re not acting entirely like remakes, many of them are doing something different from what the original series did, and I think that makes them worthwhile.

Finally, aside from the occasional Jeff Williams insert song, Irone Toda and Kazuma Jinnouchi did a great job with the music, and this probably my favorite from either of them (they often work as a duo).

Ultimately, RWBY: Ice Queendom is a difficult series to wrap my thoughts around. There is a lot of genuinely very good artistry despite the limitations of its production circumstances, and there are some genuinely very interesting and good narrative points; but those circumstances and the underutilized elements in the story itself–despite the story concept’s planned length being shorter than a full 12-episodes–ultimately are a hindrance in the long-run. I don’t think it’s bad or a disappointment, but rather something that simply didn’t know how to fully make use of the potential in its concept. I think I’ll definitely remember the show somewhat fondly, though.

Images ©2022 Rooster Teeth Productions, LLC/Team RWBY Project

Participate In Discussions