A glance at social media as of late is bound to be rife with criticism against certain journalists and gaming personalities, as well as jabs at poorly aged, if not racist clips from the G4 review show X-Play. These have stemmed results of recent comments from Square Enix producer Naoki “Yoshi-P” Yoshida. On February 28, 2023, he remarked to YouTube channel Skill Up, during a Gematsu roundtable about Final Fantasy XVI, that the game shouldn’t be called a Japanese RPG at all due to how it “was like a discriminatory term”.

Digging deeper, however, reveals that this backlash over the discrimination of JPRGs is just the latest manifestation a long-simmering war. Once thought to have been relegated to the past, it’s not only very much alive, but has left an impact on the Japanese gaming industry.

A Sordid, “Problematic” History

First emerging in the early 1980s, JRPGs evolved in response to the growing focus among Japanese developers towards consoles:

- The original Dragon Quest for the NES/Famicom in 1986 helped pave the way for future franchises such as Final Fantasy, Fire Emblem, Phantasy Star, and Persona.

- JRPGs would explode into a multimillion-dollar juggernaut in the coming decades, with myriad subgenres

- Outside Japan, JPRGs came to be beloved by Western audiences and developers in the 1990s and 2000s.

As “Seventh Generation” consoles like the PlayStation 3, Xbox 360, and Nintendo Wii came to store shelves, however, the atmosphere sharply changed. Although it remains unclear what the original catalyst was, it was already present as early as 2006, when popular webcomic Penny Arcade noted how media outlets were unfair towards Enchanted Arms, a JRPG made by a then-niche studio called From Software. A now-anonymous Venture Beat author on May 13, 2009, observed how many of the same journalists who once applauded such works were actively lambasting them, whether for being “too traditional” and “too linear,” or for supposedly bland androgynous characters. X-Play‘s mocking riffs from that time, in hindsight, were just the tip of a deep iceberg.

What arguably escalated the situation was a Destructoid interview with BioWare co-founders Ray Muzyka and Greg Zeschuk from December 18, 2009. Zechuk lamented the “fall” of JRPGs due to how they seemed complacent compared to Western RPGs like the then-upcoming Mass Effect 2, and “delivering the same thing over and over.” As they explained in more detail a few months later for IndustryGamers, the two developers bemoaned how their Japanese counterparts were being left behind, coasting off old successes rather than innovating in the way series like Fable or Fallout were doing, while implicitly suggesting that “cultural differences and the tastes of the Japanese gamers” were also at fault.

That already-simmering contempt quickly took on a life of its own, as game journalists and other personalities joined in trashing not just JRPGs, but the Japanese gaming industry as a whole:

- January 18, 2011: IGN’s Tim Henderson lamented “Japan’s decline”, citing reasons ranging from companies being unable to meet the rising costs of game development or pander to Western tastes, to insular mindsets seemingly out of touch with wider trends.

- March 6, 2012: Fez creator Phil Fish declared that modern Japanese games “just suck” in response to a question by Makoto Goto, known for his work on titles as varied as Armored Core 4 in 2004 and AI: The Somnium Files in 2019. This dismissive sentiment was reportedly shared by others on the same panel, including Braid creator Jonathan Blow.

- August 17, 2012: Alex Hutchinson, creative director at Ubisoft for the Assassin’s Creed franchise, claimed in an interview with CVG that there had been “subtle racism” in favor of Japanese developers until then that was finally being corrected, while calling their stories and plots “literally gibberish” that make Gears of War look preferable.

Others, meanwhile, used the growing zeitgeist as a jumping-off point to add further criticisms of Japanese gaming’s “problematic” issues:

- April 23, 2013: Jason Schreier made a hit piece for Kotaku about how the JRPG Dragon’s Crown allegedly reflected a tasteless, 14-year-old “boy’s club” mentality among Japan’s developers.

- October 13, 2014: Polygon co-founder Arthur Gies used a review of Bayonetta 2 as a glorified platform to decry games like it as “sexist, gross pandering.”

Such scathing remarks not only caught headlines across the gaming press, but even struck a nerve within Japanese circles:

- May 18, 2010: Capcom producer Jun Takeuchi told Xbox World 360 that if his country’s gaming industry didn’t evolve or catch up with the West, “I really don’t think we have a hope in hell.”

- March 2012: Monolith Soft director Tetsuya Takahashi remarked in an interview with Nintendo Power that JRPGs had “become a form of mockery” while making allusions to the BioWare interview as damning proof. Yoshi-P’s recent comments also seem to be traced back to the same source.

- March 12, 2012: Keiji Inafune, whose outspoken stance had already gained him notoriety by the late 2000s, told Gamespot about how Japan wasn’t “taking global business seriously,” and that the way forward from being relegated to the past was to take after the “healthy” Western development scene.

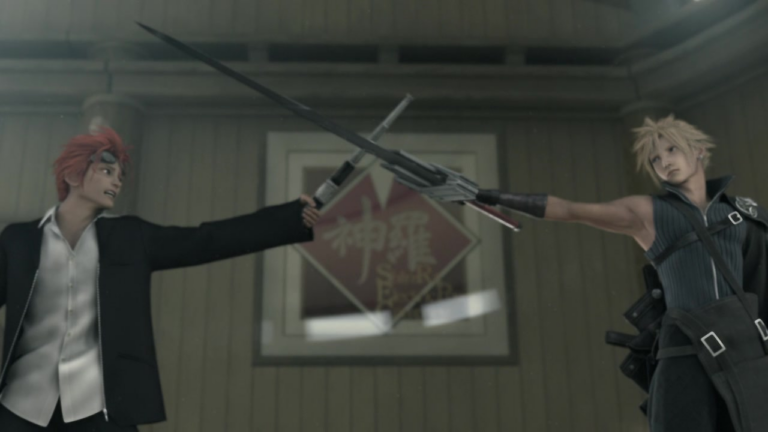

These sentiments helped influence some creators to abandon many of the Japanese “traits” that made their works beloved to begin with, in favor of elusive Western trends. The results were mixed at best, whether it was the Capcom-published DmC: Devil May Cry from 2013 feeling out of place compared to its predecessors, Inafune’s own Mighty No. 9 in 2016 being a bland frustrating mess, or 2023’s Forspoken gaining such an abysmal reception that Square Enix was forced to fold the studio that made it.

These also helped create a negative feedback loop, with Inafune’s pessimistic assessments alone being ample material for reporters. By the time The Verge’s Sam Byford published his in-depth report on the Japanese gaming industry on March 20, 2014, it’s as though that narrative had become taken for granted.

There were some other grains of truth that helped keep this narrative afloat:

- As noted by Famitsu on January 6, 2015, domestic console sales in Japan had reverted to 1990s levels by the early-mid 2010s.

- Sony’s messy launch of the PlayStation 3 in 2006 was described by then-CEO Howard Stringer as nearly “catastrophic,” seemingly lending weight to claims about Japanese companies struggling with lofty development costs.

Japan’s best days, it seemed, were well behind it. The reality, however, could not be more different.

Beyond the Narrative

Forbes contributor and Mecha Damashii founder Ollie Barder went against the grain. On February 25, 2015, he made the case that not only was there a nigh-willful ignorance of JRPGs and Japanese games in the West alongside the smears but that they served an ulterior purpose:

- Western companies, as revealed by GamesRadar’s Justin Towell in a January 11, 2013 feature piece on the PlayStation 2, were unable to directly challenge their Japanese competitors during the late ‘90s and 2000s.

- Certain developers and publishers resorted to what Barder described as “rebranding the competition as somehow culturally invalid,” with game journalists more than happy to oblige if it meant “they could position themselves at the top of a huge PR and marketing war.”

- This also helped to keep attention from how the number of AAA studios across the West had declined by as much as 80% in 2013 according to Electronic Arts data, ironically spurred in part by the same push for “innovation” and graphical fidelity that BioWare and Ubisoft were proudly touting all those years ago.

It’s worth noting as well that Western RPGs developed along a parallel path from their Japanese counterparts, rather than being inherently superior as some have suggested.:

- Western RPGs were, and to some extent continue to be made with PCs in mind, with the jump into consoles happening later, beginning with Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves in 1991.

- Even as the genre diversified and became multimedia giants, there is a general trend towards emphasizing player choice, customizability, and eventually open-world content.

At any rate, this conceit was almost brilliant in its simplicity, if not its audacity. Yet as Barder also highlighted, JRPGs, and Japan’s gaming industry, never “died” at all:

- Nintendo had enjoyed its biggest sales week in 2007 for the Wii and DS, both of which had previously been dismissed as “non-gamer” fare by Western journalists. This news would be surpassed by the Switch later on becoming the third-best-selling console of all time by 2023.

- The stigma and pessimism expressed by the likes of Inafune failed to deter other Japanese developers, finding critical success and fan support by building upon what they were already doing.

- From The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword in 2011 and From Software’s now-infamous Soulsborne titles, to the rise of new franchises like Sega’s Valkyria Chronicles, there has been no shortage of quality titles coming from Japan.

Such was their impact that by the time hits like Platinum Games’ NieR: Automata, Castlevania creator Koji Igarashi’s crowdfunded Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night, and Capcom’s Devil May Cry V came out just a few years later, some publications were forced to change their tune. Tim Henderson, who bemoaned the country’s downfall, went so far as to talk about “Japan’s revival” in a September 19, 2018 feature for IGN.

This seeming change may not be all that sincere, however, some continued to keep the flames going long after the fact, in various forms:

- August 21, 2018: Game Developer published a feature about indie RPGs in which YIIK developer Andrew Allanson boasted that Western developers like him are were pushing JRPGs forward, while LISA creator Austin Jorgensen claimed that the genre “inherently sucks because its structure makes it easier to be boring than interesting.”

- November 4, 2022: Kotaku staff writer Sisi Jiang criticized Yoshi-P and Final Fantasy XVI for allegedly enforcing a “whites-only” boundary. In a follow-up piece a few days later, the author doubled down by insisting that she does not want Japanese games to be “less socially embarrassing” and that people like her are taking them seriously.

For Their Own Good?

Ironically, underpinning many of these smears on Japanese games is this insistence by those pushing them that they are doing this for their own good. From Muzyka and Zeschuk’s takedown of JRPGs to GamesRadar’s Dustin Bailey chastising Yoshi-P’s arguments in a March 1, 2023 piece – ostensibly in defense of the genre – there’s a recurring thread of them expressing how much classic sagas like Final Fantasy had inspired them, and how they want Japan’s gaming industry to be better. At best, they reflect a paternalistic mindset.

This implicit “tough love” failed to persuade critics, and not just through social media:

- March 7, 2023: Barder made a long-overdue follow-up to his Forbes article, stating how Yoshi-P was right when he called JRPGs a discriminatory term, if only because of the hypocrisy of the very same Western commentariat, and how they seemingly remain unrepentant or unwilling to take responsibility.

- Youtubers Devon “ShortFatOtaku” Del Vecchio and Stephanie “Jimquisition” Sterling, politically mirror-opposites, both argued that those pushing the narrative in the West betray an underlying racism, stereotyping Japan as some “other” that must conform to global or “progressive” norms.

Whether out of ideological virtue-signaling or the same ulterior and financial motives observed back in 2015, these could not be brushed aside as poorly-aged jokes. Especially when they have contributed to a stigma that to some extent, still haunts discussions around Japanese gaming or culture to this day.

This discrimination has done nothing but reopen old wounds and foster new hatred. Nonetheless, history need not repeat itself. The very traits that make JRPGs and Japanese gaming at large so distinct remain as appealing for fans around the world today as when the first Final Fantasy titles made headway on American screens. As much as the behavior of certain developers and game journalists has done a disservice to both, they haven’t stopped genuine efforts by Western and Japanese creators alike to learn from one another. Even if one is not a fan, this world has more than enough room for everyone.

It is about time that this farce comes to an end and that those responsible for propagating it be put to task. Or perhaps, they should take their own advice: do better.

Written by Carlos Miguel del Callar

©SQUARE ENIX

Participate In Discussions